New flavour for Basel

Theorist and new Assistant Professor Admir Greljo connects worlds

Today we would like you to meet one of the University of Basel’s latest additions in the sciences: tenure-track Assistant Professor Admir Greljo. He joined the university’s physics department in spring and has brought lots of plans and ideas in his luggage. Find out how a childhood in a war influenced his career and how he hopes to solve the mystery of the different flavours in particle physics …

Admir Greljo is a phenomenologist. If you imagine theoretical physicists as speaking one language and experimentalists another, phenomenologists – a branch of theoretical physics – are the interpreters between the two. If theory postulates one thing and experiment finds a different thing, they turn to phenomenology for answers. If a theorist comes up with a new idea, it’s the phenomenologists who work out how it could be tested by experiments. If the data from experiments shows unusual or unexpected results, it’s the phenomenologists who get really excited in their quest to make sense of it all.

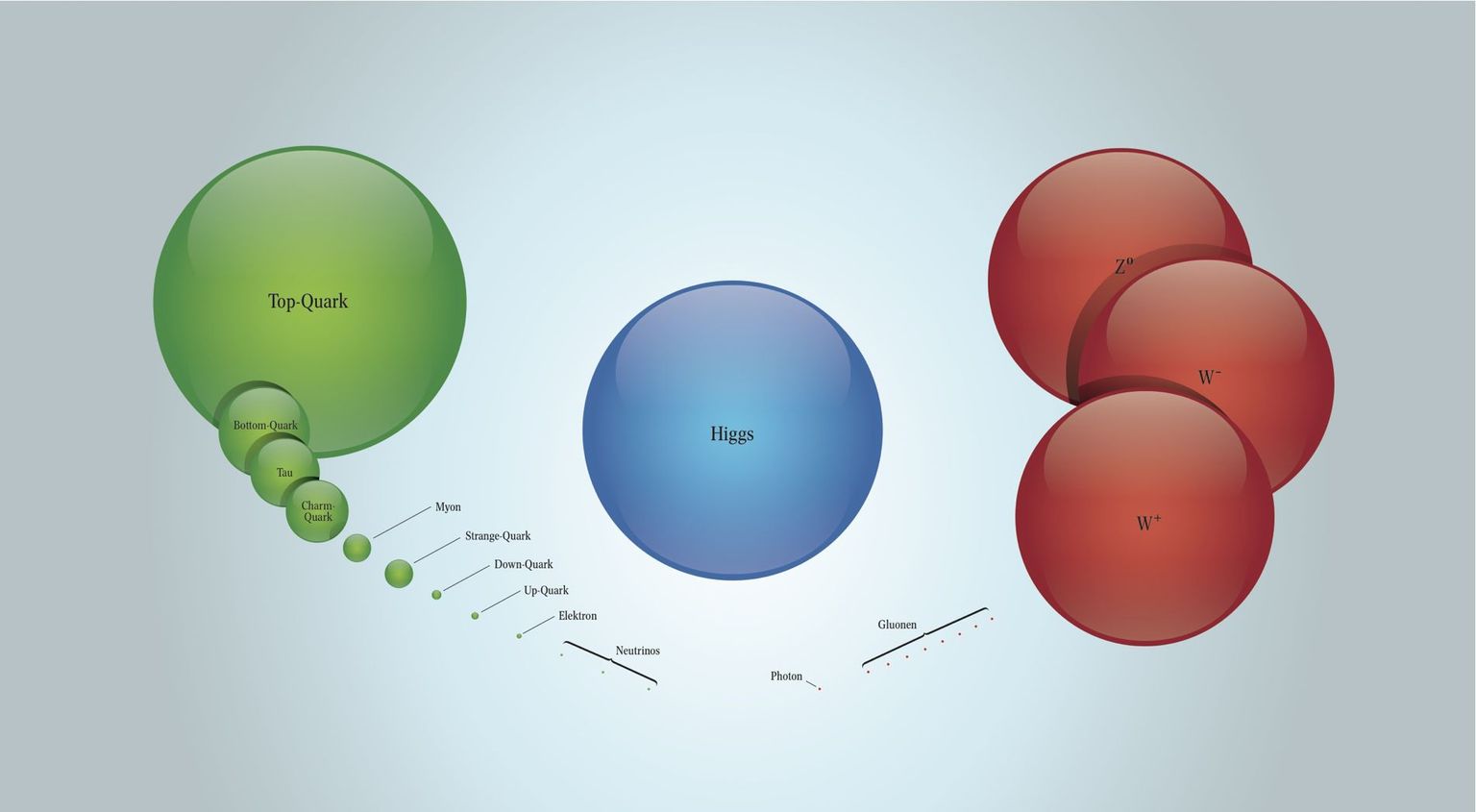

There is overwhelming experimental evidence that matter exists in three different generations, but nobody knows why – there is no theoretical explanation yet. Take quarks, for example. They come in six different flavours (up and down quarks, the lightest ones, in the first generation; strange and charm quarks in the second, and the heavyweights top and bottom in the third). Their masses are so different that they span many orders of magnitude. “There are so many puzzling questions about flavours of matter, not only their number but also the observed patterns of masses and mixings,” Greljo explains. “We just don’t know why things are the way they are…” He is in good company for choosing this particular puzzle: asked by the CERN Courier what single mystery the late Nobel laureate Steven Weinberg would like to see solved in his lifetime if he could choose, he said he wanted to be able to explain the observed pattern of quark and lepton (i.e. electrons and their heavier cousins from the other generations, muon and tau) masses.[1]

It is this mystery that Admir Greljo has set out to tackle – and a few others in its wake. But first things first. When did he know that physics was what he wanted to do in life? “I first came across physics at school in Mostar in Bosnia and Herzegovina when I was about twelve, and it clicked from day one,” he recounts. He wanted to learn more, and soon was a regular in physics competitions for students, winning lots of prizes, including a medal from the International Physics Olympiad. There was no doubt that he would go on to study physics. “I had excellent professors in theoretical physics at the University of Sarajevo,” Greljo says, but it was a course on elementary particle physics he took in his final year that really determined his professional direction.

At only 24, he had finished his PhD at the University of Ljubljana in Slovenia. It was 2014 and the physics world was ecstatic about the discovery of the Higgs at the LHC at CERN two years before. The thesis work was about the Higgs, too, diving deep into the phenomenology of this new addition to the Standard Model of Particle Physics. One of his tasks was to study how other new particles – for example dark matter – would influence the properties of the Higgs, another already tackled the Higgs in combination with the top quark.

His first postdoc brought him to Switzerland and Gino Isidori’s group in Zurich. Admir Greljo remembers it as the most influential station in his career and the time that really defined what he does today. “I started out with Higgs phenomenology, but switched focus to flavour physics” – the famous flavours had finally taken firm hold in his work. Isidori’s group was one of the first in the world to look at the problem of anomalies in b meson decays and work on related new physics concepts beyond the Standard Model related to the flavour puzzle.

Greljo’s current research tries to find connections between the different flavour-related results from the LHC experiments CMS and ATLAS to the results from the “flavour specialist” experiment LHCb to track down any similarities or telltale signs of a pattern. “It looks like there is something hidden behind these great variations in mass that we don’t understand,” Greljo says. “We try to find the explanation that makes sense of it all.”

His sense of determination and ability to put lots of energy into solving physics problems might have been influenced by his early childhood. The theorist was born in 1989 in what is now Bosnia and Herzegovina three years before the onset of the Bosnian war. His family was forcefully displaced within the country and spent long periods of time in camps and shelters. In order to have something to do, Greljo’s family members taught him to read so he read everything he could get hold of just to pass time. “It would have been unthinkable then that I would ever become a professor of physics in Basel,” he recounts. He now has a four-year-old son himself and is filled with a sense of wonder of how children get to know the world.

And here he is, setting up a growing team in Basel as a professor in physics to marry not only theory and experiment, but all the various high-energy physics experiments around the world that look at symmetries (and broken ones) in the quark realm. This is a project he brought with him from his previous station in Bern, where he set up a group under an Swiss National Science Foundation grant to look at the interplay of flavor phenomenology in different experiments at different colliders. The whole group – currently two postdocs and two PhD students, but it’s a growing team – came with him from Bern to Basel.

Before Bern and after Zurich, Admir Greljo first went to Mainz in Germany for another postdoc and then to CERN for a fellowship – “another wonderful period that really broadened my scope,” he says. The CERN theory group is one of the largest in Europe and brings together many different people of fields of expertise. Basically, it’s a big adventure playground for young (and older) theorists who can bounce ideas off one another and give each other new ideas. Greljo tried a few new things as well: “For a certain class of models, we know that the mass hierarchies can show up in gravitational waves as signals from the early Universe,” he explains. “There are peaks for every generation of quarks and there seems to be a very deep connection – but we just don’t know enough yet.” The next generation of gravitational-wave experiments like LISA or the Einstein Telescope will hopefully provide more insight. These signals from the early Universe are only one of the many things he hopes to study in his tenure-track position.

The ability to generate new ideas might be the driver of phenomenology, but it isn’t the only thing that a professor needs: managing people, hiring people, teaching and administration are all part of the everyday university experience. “I am learning the ropes,” Greljo smiles. Teaching is the part that he particularly enjoys and he is looking forward to giving his first bachelor-level course.

Greljo is happy with the way things are in the phenomenology world. “From a physics point of view, we are in a very interesting situation. The data are interesting, more will soon come from experiments like Belle II and there is important fundamental work to be done. And there’s always room for wild ideas!”

Barbara Warmbein

[1] https://cerncourier.com/a/model-physicist/